In Part Three, we looked at Hubbard’s return home from Australia and the associated mythology surrounding this journey, as well as uncovering the truth about his alleged use of Pan American’s Philippine Clipper to get from Brisbane to Honolulu and on to San Francisco.

In Part Four, we turn to Hubbard’s brief time as a cable censor, his disastrous first attempt at command and his eventual admission to the Submarine Chaser Training Center (SCTC) in Florida. We’ll look at Hubbard’s record as associated with the converted fishing trawler Mist, eventually recommissioned as the coastal patrol craft USS YP-442, as well as the Church of Scientology’s claims about his combat record in the Battle of the Atlantic. I’d like to once again thank Chris Owen in particular for his previous research, which was invaluable to me in providing much of the historical context for this post.

Hubbard the Cable Censor

Upon arriving at Treasure Island via clipper on March 23, 1942, Hubbard, with his catarrhal fever diagnosis, (in modern terms, a cold/bronchitis-like condition), most likely was transferred by USN Medical Corps bus to the US Naval Hospital (USNH) at Mare Island, Vallejo, CA, 30 miles/50 km away:

Though the 12th Naval District was headquartered at Treasure Island for the duration of the War, Mare Island Naval Shipyard was the closest major naval facility with a hospital; (Hubbard’s last naval port of call, Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, CA, would not be commissioned until June 1, 1942, and was at that time intended to be a temporary facility to handle the expected massive influx of casualties from the Pacific.)

After his discharge from USNH Mare Island, Hubbard was then detached from service with naval intelligence and sent to New York to work in the Office Of Cable Censorship, a civilian-headed organization:

A creation of J. Edgar Hoover, the Office of Cable Censorship was staffed by both civilian and military personnel. Counter to the revisionist/apologist narrative, it was not an intelligence-related function, in fact, as the following details, it was explicitly created to ensure its functions were not co-opted by the War Department:

“FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover initially headed the media relations program, while the military operated cable and postal censorship offices around the country. Hoover soon recommended the creation of a new agency with a civilian director to oversee all censorship activity. Roosevelt picked the executive news editor of the Associated Press, Byron Price, to take the lead. Price was a remarkably good choice, as it turned out. He was known among newspaper editors and reporters as a fair man. He accepted the job only after assurances that he would work directly for the President and that censorship would remain voluntary.

On 15 January 1942, Price’s Office of Censorship issued its first Voluntary Censorship Code. The Code underwent four major revisions during the war. Price put the onus for censorship directly on the journalists. His methods were to nudge and talk them into compliance under his motto: “Least said, soonest mended.” The civilian censors had no authority to excise material prior to publication or punish violators, although they could publish the names of those who stepped over the bounds. Only the Justice Department could prosecute offenders under the provisions of the 1918 Espionage Act.

Price delegated the release of information to “appropriate authorities,” meaning that those directly involved—from combat commanders to government department heads—decided what information about their activities could be made public. This kept the Censorship Office out of numerous controversies. A case in point was the famous episode in which Gen. George Patton slapped a soldier suffering from battle fatigue. Newsmen filed requests to print the story; Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, gave his approval.

The system of voluntary censorship worked. Self-censorship created a supportive culture among reporters and editors. Price worked hard to keep the system voluntary. In the middle of the war, for example, he opposed legislation that would have created an American version of the British “Official Secrets Act,” which would have decentralized the program and put every federal department in charge of its own censorship program. Price kept the Censorship Office separate from the Office of War Information (OWI), believing that combining censorship activities with the pseudo-propaganda releases of the OWI would subvert the aim of keeping the American public truthfully informed about the war. He also beat off an attempt by the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department to enforce stronger censorship of information about the military. In this the Joint Chiefs of Staff opposed Price, but he prevailed.”

A common theme in Hubbard’s early fitness reports as a naval officer was that he was unfit for positions of individual leadership, though competent in tasks when supervised. Chris Owen goes on to state that:

“As predicted, he was indeed better suited to this job with the Chief Cable Censor’s Investigations Department and received a positive report (but only average marks) from his superior, Commander Andrew Cruise:

Since reporting to this activity this officer has shown a full realization of the seriousness of an assignment to duty. He has shown an increasing sense of responsibility and displayed a marked improvement in his work. While the period of observation has been short, his work has been entirely satisfactory.

(Source: Report on the Fitness of Officers, L. Ron Hubbard #113392, May 11 1942 – June 24 1942)”

Hubbard’s Hits the Hospital Yet Again…

Hubbard labored in obscurity censoring message traffic and other communications, and on May 11, 1942, was seen at the US Naval Hospital at the Brooklyn Naval Yard, where he is diagnosed with actinic conjunctivitis. Actinic conjunctivitis is defined as “an inflammation of the conjunctiva (the mucous membrane that covers the front of the eye and lines the inside of the eyelids) and is caused by exposure to the ultraviolet radiation of sunlight or other sources, such as acetylene torches, therapeutic lamps (sun lamps), and klieg lights. Also called actinic ophthalmia.”

The medical report states that Hubbard questions his ability to use his eyes continuously because of “eye strain during exposure to tropical sunlight.” His also complains of a “sprained left ankle,” which he will later spin as as foot fractures resulting from his proximity to bomb explosions on a steel-decked warship, more of which we’ll discuss in a future post.

However, this diagnosis raises a couple of questions. First, Hubbard was originally admitted to USNH Mare Island with a diagnosis of catarrhal fever, the symptoms of which he’d said had “come on” four days prior to his arrival from Honolulu. As previously noted, catarrhal fever was something of a catch-all diagnosis at the time for upper respiratory ailments. More so, rather than having falsified a set of expedited travel orders as posited in our previous post, there are indications that Hubbard could have either falsified a medical chit exaggerating his condition so as to expedite his trip home via Pan American Clipper, or persuaded a harried naval doctor at Pearl Harbor to provide the needed chit.

But why then is his conjunctivitis not also noted at the same time, seeing that he blames it on exposure to tropical sunlight? He is after all returning from the Southwest Pacific, yet the way the diagnosis is written, it would appear that the MD or corpsman who saw Hubbard at USNH Mare Island took his self-diagnosis at face value, as there’s not a lot of symptomatic difference between common conjunctivitis and actinic conjunctivitis.

I would argue that he contracted common conjunctivitis, usually described as “pink eye” either on the MV Pennant on his way back from New Caledonia, or more likely, on a crowded troop train from the West coast to his cable censor duty station in New York. His orders have him leaving April 29th, 1942 via “1st Class from San Francisco, Calif. to New York, N.Y. via SP Ogden-UP CBlfs-C&NW Chi PnRR.” Thus as an officer, Hubbard would have had better seating and not been packed-in with the enlisted men. However, the sheer number of soldiers, sailors, and Marines being transported via rail at the time almost guaranteed that Hubbard would have been exposed to all sorts of communicable diseases, “pink eye” being but one of the many, extremely common hazards of these crowded conditions.

Hubbard Takes Command, and Sinks in Boston

Hubbard’s time as a cable censor was unremarkable, highlighted by repeated demands for payment on past due bills from the First Bank of Ketchikan, Alaska and his Brisbane tailor. He does receive a satisfactory fitness report for his work, and to his credit, on June 10th, 1942, he requests to be transferred to sea duty. He makes his case with typical Hubbardian bravado:

On June 22nd, 1942, he gets his wish, and is assigned his first command, a former fishing trawler, the Mist, soon to be converted as a coastal patrol vessel commissioned as the USS YP-422. It’s here we see the origins of his first fibs in this, the “Battle of the Atlantic” chapter in his military mythology.

His orders tasked him with supervising the Mist’s conversion at the George Lawley & Sons shipyard, Neponset, Mass. Given Hubbard’s ongoing contentious relationship with the civilian dockyard workers and perennially inflated sense of self, his interlude here would eventually end in tears due to the final straw, a conflict with the Commandant of the Boston Navy yard.

Despite Hubbard’s entreaty to the Vice Chief of Naval Operations (see below), wherein he states “my vessel in condition superior to any other in division,” he’s relieved of command of the USS YP-422 on October 1st, 1942. Aside from his conflict with the head of the Boston Navy Yard, his going several levels above the head of his superior officer directly to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) was about as big a military faux pas as one could commit; if Hubbard’s command was barely afloat before this missive, he undoubtedly torpedoed any chance at redemption with this little gem:

True to form, the Church of Scientology spins this episode as Hubbard’s first combat command, and in doing so, laughably inflates both Hubbard’s competence and the YP-422’s capabilities. Chris Owen sets the stage:

“The Church of Scientology has claimed, and continues to claim, that L. Ron Hubbard’s service in the North Atlantic was aboard one or more ‘corvettes’ or ‘an anti-submarine escort vessel with Atlantic convoys’. The claim originates with Hubbard himself, who stated that one week after being admitted to hospital in Vallejo, California in ‘Spring’ (actually April) 1942, ‘they ordered this casualty to duty in command of a corvette in the North Atlantic’. Scientology has in recent years alternatively claimed that Hubbard’s vessel, the USS YP-422, was a ‘hastily fitted subchaser.’

All of these claims are, in fact, totally incorrect. Hubbard’s vessel, the USS YP-422, was neither a corvette nor a subchaser but a converted trawler, responsible for patrolling coastal waters rather than escorting convoys across the North Atlantic.”

Hubbard Chases Glory But Not U-Boats…

You’ll remember that America’s defense posture was woefully inadequate at the beginning of WWII. Prior to Germany’s official declaration of war on the United States on December 11, 1941, she’d been violating her official position of neutrality in assisting the British via Lend-Lease and more directly, in convoy escort duty in the North Atlantic. Even with this early battle experience, the US Navy at the time was woefully under-equipped to counter the significant German U-Boat threat and even more so once war was officially declared.

The Navy’s ability to protect vital convoys to Russia and Britain, as well as the Nation’s coastal shipping was severely impacted by a lack of dedicated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability in the form of coastal patrol craft, destroyers, and other dedicated ASW platforms. The Navy called for a huge conversion of civilian shipping stocks into all manner of quasi-ASW shipping until this capability gap could be met by industry, eventually resulting in a staggering diversity of ASW and patrol vessels by 1943.

The severity of this ASW capability gap could have lost the Battle of the Atlantic, and even the war in Europe. It took the United States almost two years to establish a war footing on the Eastern seaboard, including proper blackout discipline, productive air and naval ASW patrols, and the effective use of convoys to foil the U-Boat threat. Light discipline was so poor at one point that American coastal oil and transport shipping was backlit by brightly lit coastal cities, allowing U-Boat captains spectacularly successful targeting capabilities as a result. Such was their success on the Eastern seaboard and in the North Atlantic as measured in tonnage sunk, that this period in the Battle of the Atlantic was referred to by Kriegsmarine submariners as “the Happy Time.” The Battle of the Atlantic would be the longest running battle of the war in either theatre; it ran from September of 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.

It was during this dire time that Hubbard would assume command; the US Navy deployed a hodge-podge of equipment in 1942: a mix that consisted primarily of converted civilian shipping, WWI-era four stack destroyers, (ironically, including the same Clemson-class destroyers as the USS Edsall, Hubbard’s phantom ride from his Java caper), US Coast Guard cutters, and limited aviation resources including blimps. Thus Hubbard’s ship was a vital stop-gap to some extent, despite it’s rather less-than imposing appearance.

The Church of Scientology claims Hubbard skippered a “corvette,” even though they weren’t in widespread US Navy service at the time, and when finally acquired in any quantity, numbered a scant 8 in service out of an original order of 25. Furthermore, the USS YP-422 (top) didn’t remotely resemble a USN Patrol Gunboat (PG-Class) corvette (bottom) in size nor capabilities, as the following photos illustrate:

Once the US’ ship building program kicked into high gear, American shipyards turned out thousands of destroyers (DD), destroyer escorts (DE), and dedicated sub chasers (SC) which were the war’s preferred ASW platforms; therefore, American use of corvettes was essentially a sidebar to the US Navy’s participation in the Battle of the Atlantic:

“In December 1941, after the US entry into World War II, the USN had a large building programme for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) ships, but none nearing completion. To overcome this shortfall, the Royal Navy agreed to transfer a number of ASW ships to the USN, including ten Flower-class corvettes. These ships had already been in commission and had seen action during the Battle of the Atlantic.

These ships were classified as Patrol Gunboats, and numbered PG 62 to 71, and were referred to as the Temptress class, after the first ship to be re-commissioned. The USN also placed orders for 15 more Flowers from Canadian shipyards. This was met by transferring a number of vessels on order for the RN to USN. These ships were of the Modified Flower type, a design which consolidated the various modifications developed in the course of building the original Flowers.

In the event the USN only took charge of eight of these ships; the other seven were transferred back to the RN under Lend-Lease arrangements. The US ships were numbered PG 86 to 100 and were referred to as the Action class.”

The Flower-class corvette was the predominate convoy escort early in the war, and used primarily by the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy. The only difference in corvette usage between the two navies was that:

“Royal Navy corvettes were named after flowers, and ships in Royal Canadian Navy service took the name of smaller Canadian cities and towns. Their chief duty was to protect convoys throughout the Battle of the Atlantic and on the routes from the UK to Murmansk carrying supplies to the Soviet Union.

The Flower-class corvette was originally designed for offshore patrol work, and was not ideal as an anti-submarine escort; they were really too short for open ocean work, too lightly armed for antiaircraft defence, and little faster than the merchantmen they escorted, a particular problem given the faster German U-boat designs then emerging. They were very seaworthy and maneuverable, but living conditions for ocean voyages were appalling. Because of this, the corvette was superseded in the Royal Navy as the escort ship of choice by the frigate, which was larger, faster, better armed, and had two shafts.”

Besides never having skippered a corvette, what’s perhaps more absurd is Hubbard’s contention that his crew somehow resembled some nautical version of “The Dirty Dozen,” or more appropriately, a WWII version of Jack Sparrow’s band of brigands. For the record, Portsmouth Naval Prison in Kittery, Maine, was the preferred home for hardened naval criminals, not warships, during WWII:

There is no record of ANY naval vessel being crewed by criminals during the war, civilian, military, or otherwise. Once again we refer to Chris Owen’s Ron the War Hero, where he quotes Hubbard from one of his lectures, as well as providing further context:

“But Hubbard’s biggest problem was the crew:

… Unofficial naval policy was to man [such vessels] with only expendable crews. Consequently, upon entering the Boston Navy Yard, Ron found himself facing a hundred or so enlisted men, fresh from the Portsmouth Naval Prison in New Hampshire. A murderous looking lot, was Ron’s initial impression, “their braid dirty and their hammocks black with grime.” While on further investigation, he discovered not one among them had stepped aboard except to save himself a prison term. (Source: L. Ron Hubbard: The Humanitarian, Church of Scientology, 1996)

The impeccably humanitarian Hubbard apparently told his ‘ex-convict’ crew that all slates were now clean and all past crimes immaterial, whereupon he drilled them until “these men were standing sea watches in undress blues merely because they thought it would look better”. After only six weeks they had been transformed from criminals to superb seamen – according to another Scientology account, the finest in the fleet – ‘with some seventy depth charge runs to their credit and not a single casualty’.

The author of this work appears to have gotten somewhat confused at this point, as Hubbard’s much-vaunted depth charge runs were actually made aboard a completely different ship in a different ocean at a different time, the Pacific-based subchaser USS PC-815 in May 1943. Needless to say, the claim that he captained a ship of criminals has never been corroborated.”

Further Myths of the USS YP-422

In keeping with it’s coastal defense role, the USS YP-422 was lightly armed with only a 3” crew-served gun on the fo’castle, and two .30 cal machine guns and NO depth charges… Hardly a fitting arsenal for a band of ruthless jailbirds, let alone one formidable enough to take on the U-Boat menace. His use of “clean slates” is interesting, and represents perhaps the first iteration of the many amnesties he’d grant his Sea Org crews in the ‘70s, as well as alluding to them “looking smart,” wherein it would seem that appearances superseded competence in his mind. In keeping with his Australian adventure, we have yet another fanciful tale of his command competence and Hubbard as martial miracle worker among these wanting military professionals.

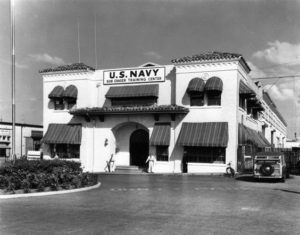

The reality was that having been cashiered from his first command, he would now cool his heels at the Naval Receiving Station (NRS) Long Beach, Long Beach, Long Island NY. A NRS was a clearinghouse for personnel in transit to a new duty station, or served as a temporary command while new orders caught-up with an individual among other functions. While here, Hubbard successfully requested a transfer the Submarine Chaser Training Center (SCTC) and began his training there, in this facility, on November 9th, 1942:

The SCTC was set-up at the Port of Miami, FL in March of 1942 as a result of the massive expansion in USN ASW capability, primarily as a means to expedite the training of the naval reserve officers and men who would provide the vast majority of crews for these diverse new ASW vessels. Hubbard would also meet Lt. Thomas Moulton while stationed here, a friendship that would be of great significance to Hubbard both during the war, and later as head of Scientology. Having requested duty on “PC Boats, patrol’ in ‘Caribbean or Gulf,” Hubbard, according to Chris Owen, enjoyed the salubrious Florida climate:

“(He) fitted in well at the SCTC, though he seems to have regarded his posting there as a cushy break. He recalled his time there in a 1964 lecture, “Study: Evaluation of Information”, commenting that “it was a lovely, lovely warm classroom, and I was shipped for a very short time down into the south of Florida… and, boy was I able to catch up on some sleep.”

Hubbard Takes Command (again…)

It would appear that Hubbard may have caught-up on some of that sleep in the classroom, having graduated 20th out of a class of 25, but that was good enough to qualify for posting to a PC-461 Class 173’ steel hull patrol craft, the USS PC-815:

On January 13, 1943, Hubbard was directed by telephone and subsequent confirming memorandum, to “proceed without delay to Portland, Oregon, and to report to the Commandant, Thirteenth Naval District, for duty in coordination with the fitting out of the USS PC-815 at the Albina Machine Works, and for duty as commanding officer of that vessel when placed in commission.”

In Conclusion

Hubbard’s eventual duty as the skipper of the USS PC-815 represents the final disaster in the series of calamities that marked his time in the surface navy, prior to his eventual hospitalization at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, CA. In Part Five, we’ll look at the series of events leading up to “The Battle of Cape Lookout, “ where he claimed to have engaged and damaged and/or sunk two Japanese mine laying submarines, and later, his apparent fun with deck guns south of the border, when he shelled the Mexican-owned Coronados Islands of off Baja California. Hubbard’s follies afloat were truly a case study in command incompetence across the board; more so, his efforts as skipper of the USS PC-815 reflected an ongoing comedy of errors unique for the period as we’ll see in my next post.