Today in part 5 of our ongoing series on Hubbard’s dismal naval career, we examine the “Battle of Cape Lookout”, wherein he claims to have damaged and/or sunk two Japanese subs off the Oregon coast. It builds on the work of Chris Owen and Jeffrey Augustine and also draws on additional official US Navy records, and refutes some of the arguments of Hubbard’s apologists that attempt to shore up his Navy record. In doing so, we may have uncovered new evidence of Hubbard falsifying events beyond those previously exposed as fiction. The events here cross the line from normal incompetence to a Walter Mitty-like delusional fantasy, where, in the space of 55 hours at the helm of the USS PC-815, Hubbard attacked two Japanese submarines that existed only in his imagination. The narratives that emerge from this event provide a powerful foreshadowing of Hubbard’s pattern of lies, self aggrandizing fantasy and fraudulent conduct that would define so much of his later life, especially in regards to his military service.

In many ways, the events that occur over the roughly 80 days of Hubbard’s command of the USS PC-815, a PC-461 class patrol vessel and his subsequent spin on these events, provides more fodder in perpetuating all the myths, lies, half-truths and fraudulent misrepresentations Hubbard repeats ad nauseum about his previous 3 years in the Pacific. In our usual fashion, we’ll be providing additional analysis and historical context to the existing record in deconstructing and exposing the fantasy that was his fight off the Oregon coast over the 21st, 22nd and 23rd of May, 1943. We’ll also expose what we believe is an attempt to cover up specific incidents of Hubbard’s incompetence and his crew’s negligence that could have proved fatal. It makes for a rather interesting wartime tale, a tale rife with incompetence and as his after-action report demonstrates, a level of histrionics that reflects typical Hubbardian shirking and unconscionable scapegoating and badmouthing of his fellow officers.

The USS PC-815 Goes Forth

You’ll remember from Post 4, that after graduating 20th out of a class of 25 from the Submarine Chaser Training Center (SCTC) in Port Miami, FL, Hubbard was then assigned to the Albina Engine and Machinery Works in Portland, OR, to oversee the completion of the USS PC-815. Upon her commissioning, he was then to assume command. She was first laid down on October 10, 1942, with Lt. (jg) Hubbard assuming command on April 20, 1943. The 815’s beginnings were not auspicious, as on her way up the Columbia river to start her sea trials, she fouled her propeller somehow, causing a week’s delay to her arrival at the Naval shipyard located in the port of Astoria, OR on or around May 17th, 1943. The following photo on the top was taken by the Albina Works’ and shows the USS PC-815 prior to her final weapons fit, while the bottom photo shows a 461-class fully outfitted:

After a spell in drydock to repair her propeller, she returned to Astoria and received her initial depth charge and deck gun complement, along with ammunition and other warfighting stores. Chris Owen provides some context as to the USS PC-815’s commissioning and an entertaining bit of PR fluff from the time:

“At 10 a.m. on Tuesday April 20, 1943, the USS PC-815 was commissioned. Hubbard and the rest of the crew signed the logbook to register their reporting aboard for duty. Two days later, as the ship was being tested and readied for sea, the Albina Engine and Machine Works held a photo-opportunity for the Oregon Journal. Moulton and Hubbard were photographed in their sea jackets (below), Hubbard posing with a suitably nautical pipe rather than his usual Kool cigarettes. The article was certainly entertaining, if more than a little inaccurate:

Ex-Portlander Hunts U-Boats Guides New 'Hell Howler'

|

“There can be no doubt that the primary source of the personal information on Hubbard was Hubbard himself – there could have been no other source. Some strange inaccuracies appeared to have crept in, however.”

Owen goes on to expose all the various exaggerations and fibs Hubbard includes, of which here’s a sample:

“Hubbard was not even a full Lieutenant, let alone a Lieutenant Commander. Having only been temporarily promoted, his substantive rank at the time was still Lieutenant (junior grade). His father was a Lieutenant Commander but was demoted to lesser rank in the article. His grandfather “Captain” Waterbury had been a small-time vet and coal merchant and had never served afloat. “I.C. De Wolfe” was in fact the maiden name of Hubbard’s grandmother, Ida Corinne, not his great-grandfather, John DeWolfe, who had been a wealthy banker. Hubbard had not participated in either the Battle of the Atlantic or the Pacific. His youth was spent not in Portland, but mostly in Helena, Montana, Washington, D.C. and Bremerton, Washington State. He had, of course, never visited most of the world’s seas and oceans (nor did he in later life).”

The 343 461-class PCs built between 1941-1944 were among the many diverse utility, patrol, assault, and amphibious warfare vessels churned-out by the nation’s shipyards in WWII. Some were wooden-hulled, especially those used for mine warfare, as were the most famous of these patrol vessels, the patrol torpedo, or “PT” boats, one of which, PT-109, was heroically skippered by future president John F. Kennedy. The 461 PC class were steel-hulled and relatively robust ships, though their crews lived in cramped quarters surrounded by weapons and machinery. The PCs were purpose-built sub chasers with no frills, designed specifically for coastal anti-submarine (ASW) warfare; the Navy would also modify 56 hulls for different patrol duties, further demonstrating the utility of the design.

The USS PC-815’s war officially began when she was diverted during a trip from Astoria to Bremerton Naval shipyard, and tasked with searching for a downed Naval aircraft off the Oregon coast. Having spent a day looking for the downed flyers, she was then re-tasked with orders to proceed to San Diego, rather than returning to Bremerton to receive her final weapons and radar outfit. It was during this redeployment that Hubbard’s infamous “Battle of Cape Lookout” occured. Chris Owen has mapped her track on this voyage:

How Significant Was the Threat?

Japanese submarine activity early in the war was not unknown in US waters. They were especially aggressive around Hawaii, and active off the shores of Southern California and the Pacific Northwest. The Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) fleet operations in the greater Pacific Ocean against the Dutch, British, Australian and United States Navies was codenamed Kido Butai, (“Mobile Force”), as were the forces that were to execute the operation. The Kido Butai was comprised of two elements, the main, or “first force” was called the Advanced Force, which was tasked with destroying the main US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor before it could sortie to counter IJN operations in the Southwest Pacific. The attack element at Pearl Harbor included a significant component of two-man mini-submarines, and their mother subs and escort vessels. Submarine operations were considered a vital combat element in support of IJN surface operations and continued until the end of the war. Japanese submarine operations in the Northern Pacific were directed primarily from Kwajalein Island in the Central Pacific, as well as being logistically supported by submarine tenders at sea.

At the outbreak of the war, the Japanese had one of the largest and most varied operational submarine fleets among the major powers and represented a significant threat to the Western United States;, she had developed impressive long-range capability that was augmented with a unique aviation capability on certain classes of submarine, further extending the IJN’s reach in the Western Hemisphere. However, though a submarine power early in the war, by 1942, Germany’s far greater industrial capacity had eclipsed Japanese submarine construction, certainly in ocean-going classes of submarine. To give you an idea of the disparate industrial capacity between the two nations, through May of 1945, Germany had built over 1,000 ocean-going U-boats of various types, to Japan’s 150 ocean-going submarines; this equates to roughly 37 new hulls per year over the 4 years of the war against the United States. In spite of these industrial inefficiencies, the IJN submarine fleet represented a significant threat up until the end of the war. Indeed, Japanese subs shelled a refinery in southern California, a fort at the mouth of the Columbia River, and sank 10 merchants ships, as well as damaging 7 more, all along the Western seaboard.

The Japanese also attempted to mount two submarine-launched air strikes, a feat unmatched by either side in the war. The first, launched from the I-25, a B-1 Type, I-15 class sub on Sept. 9th, 1942, used a Yokosuka E-14Y “Glen” floatplane. Launched from a temporary forward mounted catapult, the Glen successfully dropped two 168 pound incendiary bombs in Oregon forest land near Brookings, causing minimal damage. The second was to be a strike on the Panama canal, using the largest subs built by any WWII combatant, the purpose-built I-400 class aircraft-carrying submarines. They could stow up to three Aichi M6A Seiran (“Clear Sky Storm”) floatplanes, capable of carrying a 1,800 lb bomb 620 miles at 295 mph. These were monster subs, over twice the size of contemporary American subs, with a length of 390-feet and displaced 5,900 tons. The aircraft hangar located amidships was 102-feet long and 11-feet in diameter. These subs were capable of incredible range, and were able to circle the globe one-and-a-half times on a single fueling; in the later, desperate stage of the war, several I-400 class subs made the round-trip to Germany to obtain jet technology, gold, and other vital war supplies for Japan.

Despite such technological innovations, the IJN submarine fleet was not a game-changer. The small lots in which Japanese submarine classes were constructed, as well as a doctrinal bias against submarines as a distinct class of offensive combatants, denied the IJN’s submariners the ability to hunt in “wolf packs” and to range independent of the surface fleet, as was the case with the Kriegsmarine and US Navy. Individual IJN captains enjoyed isolated individual successes during the early major surface engagements of the war, such as during the battles of the Coral Sea, Midway, and Santa Cruz islands. However, they never remotely approached the large tonnage claims of German submariners during the height of the Battle of the Atlantic, and certainly never approached the tonnage sunk by US submarines in and around Japan’s home waters from late 1942 on.

Given the high attrition of IJN submarines throughout the war, their overall effect on US Pacific naval operations were minimal; by 1943, Japanese submarine operations were few and far between, and mostly undertaken closer to the home islands. This was due mainly to having lost operational bases to the American “island hopping”campaign in the Central Pacific, as well as US submarine successes in sinking their tenders, oilers and other support ships. More so, contrary to IJN doctrine, the US pursued aggressive, highly successful ASW operations in the Pacific, an outcome of the hard-learned lessons of the “happy time” during the Battle of the Atlantic. With this historical background in mind, let’s now take a look at the likelihood of one, let alone two relatively rare IJN mine-laying subs lurking off the Oregon coast in late May, 1943.

Hubbard Takes on the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Battle of Cape Lookout began early on the morning of May 19th, when one of the 815’s sonarmen reported a contact at 0340 hours. Hubbard immediately assumed this to be evidence of the presence of “an enemy submarine” and would have ordered “general quarters – man your battle stations.” With a loud klaxon sounding general quarters, her crew would have assumed their battle stations, including her depth charge racks, “K-gun” and Oerlikon 20 mm anti-aircraft mounts, main 3”/50 deck gun mount, damage control stations, and other vital posts. Hubbard would have most likely been on the bridge, with his “talker” (a seaman tasked with relaying his commands via internal telephone) relaying updates from the sonarmen and other vital areas of the ship.

Executive officer Lt. Thomas Moulton would have been responsible for ensuring the ship was ready for combat and updating Hubbard with the ship’s combat readiness throughout the upcoming “battle.” Given this period in the war, Hubbard’s 59-man crew was most likely comprised mostly of volunteers and some draftees, all supervised by 4-6 regular navy petty officers and four commissioned officers. We have no record of the performance of each individual enlisted man, though in retrospect, it seems collectively rather spotty in certain areas such as gunnery, sonar methods, and weapons maintenance as we’ll discuss further on. These contemporary photos give you an idea of what the PC-815’s crew would have looked like at general quarters:

Small boat operations presented their own unique challenges relative to destroyers, cruisers and larger ships, which were blessed with entire departments dedicated to what one or two sailors on the PC815 might be responsible for. A sailor who had gone through boot camp and then specialist “A” school training, was expected to have subject mastery in not only his “rate” or specialty, but also a sound working understanding of all the primary duties on his ship, regardless if he was a machinist’s mate, gunner’s mate or sonarman.

Arguably, given the ad hoc nature of Hubbard’s naval duties, training, and cumulative experience up until he was formally schooled at the SCTC, it’s more than likely his crew was far better prepared for the exigencies of small boat operations than he ever was. In additional to their ratings expertise, sailors were expected to have an encyclopedic knowledge of the Bluejackets’ Manual, the bible of all things naval for enlisted personnel as well as absorbing a huge body of unwritten knowledge from “the old salts.” I doubt that Hubbard, given his own exaggerated opinions about his nautical expertise, ever cracked the officer’s version of the Bluejacket’s Manual, entitled Seamanship. As we’ll see, the after-action narrative Hubbard supplied is true to form, and bore little resemblance to the events as reported by other participants. Not surprisingly, he was later officially sanctioned for not adhering to the proper ASW after-action reporting format by his superiors. However, that was the least of his many errors and omissions within a narrative that exposes a contempt for doctrine and poor tactical execution, inflexible decision making, and poor personal judgement.

In an earlier post, we noted the efficiency of the Navy’s personnel management system, that even in wartime, can determine with a great deal of certainty where a particular individual is or should be. The same thoroughness holds true in ensuring that a vast wealth of doctrinal publications, technical manuals, instructional pamphlets and other documentation are available to ensure everyone, from the CNO on down, knows their job and how to do it in any circumstance. As a former intelligence officer, Hubbard was certainly aware of all this knowledge, though it appears his only formal exposure to ASW doctrine and tactics was during his brief stay at SCTC and his performance bears this out. To fill any knowledge gaps, he could have referred to any of the 25 different publications concerning ASW weapons, tactics, and SONAR procedures for patrol craft and sub chasers, as well as the foundational materials relative to basic naval tactics, ship handling and relevant technical specifications.

Then there’s all the documentation regarding enemy tactics, equipment and personnel. Every week, in both the Pacific and European theatres, a small intelligence digest was provided to those in a combatant role across all the services. This concise format supplemented all the classified daily intel summaries, upcoming ship movements cables, and technical intelligence about new Japanese tactics and weapons that comprised the daily intelligence summary. For any skipper and his XO, this was in addition to managing the volume of day-to-day communications, log entries and other minutiae of life at sea in wartime. Despite all these intelligence, technical and doctrinal resources, it still comes as no surprise that Hubbard managed to make a mess of things; inexcusably, he looks to have been winging it the entire time, as he never was big on details nor did he ever acknowledge his ignorance on any matter. Thus sheer force of will does not a successful skipper make.

The Difficult Art of Anti-submarine Warfare

The heart of the matter lies in the validity of the 815’s alleged SONAR contact, coupled with Hubbard’s lack of tactical acumen, and the unavailability of any supporting evidence as to his after-action claims. We know that Hubbard had undergone basic SONAR training as part of his SCTC course, though ultimately, the accuracy of any contact was a function of the hardware’s reliability, the training of the 815’s sonarmen, along with Hubbard’s ability to analyze and process these variables into a reasoned command decision. Chris Owen has written a detailed overview of the events in question, the complete version of which can be found here. For our purposes, we’ll be selectively deconstructing the after-action report as well as the official investigation that occured at command level, and continuing to draw on Chris’ work at length in analysing Hubbard’s command decisions and behavior in action.

With those factors in mind, let’s first look at the state of SONAR and basic ASW tactics in 1943. The following examples are taken from the Chief of Naval Operations’ (CNO) after action report on ASW operations in WWII and provide a detailed description of just how difficult it is to detect, let alone sink a submarine. The information here helps to further expose the rather cavalier approach of Hubbard’s attack, given the challenges involved and the seriousness of the potential threat, knowing he was only some 10 miles off the coast of Oregon. Hunting subs involves a very deliberate calculus; had a legitimate threat existed, there’s a high probability that his incompetence could have resulted in the intra-coastal sea lanes along the Oregon coast being denied to merchant and military shipping, as a result of Japanese sea mines.

Let’s now look at just how difficult the detection process is:

“From the theoretical point of view we are interested primarily in attacks against submerged submarines, though an anti-submarine action often involves gunfire or ramming when the submarine is surfaced. The submarine may have been detected on the surface initially, or it may have been forced to the surface by previous attacks. In either case the ensuing action on the surface is little different from any other surface action and needs no consideration here.

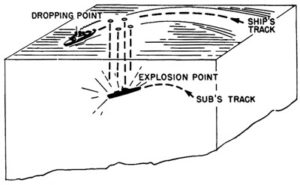

FIGURE 1. Stern-dropped attack.

When the presence of a submerged submarine has been detected by sonar, the initial step in the attack is to “localize” the submarine, i.e., to determine its range and bearing from the attacking ship. On the basis of continuing range and bearing data, the submarine must then be “tracked” in order to determine its course and speed. Sometimes this is done explicitly by plotting positions, but more often it is done implicitly. Finally, the attacking ship must maneuver into a position such that when it launches its explosives they will reach a point beneath the surface at the same time as the submarine reaches that point. Figure 1 illustrates a typical attack in which the barrage is laid off the stern and to the quarters of the attacking ship, and Figure 2 illustrates an attack in which the explosives are thrown ahead of the attacking ship.

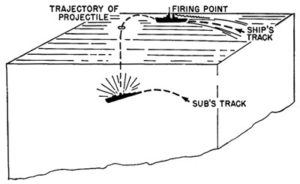

FIGURE 2. Ahead-thrown attack.

These explosives may be activated by contact fuzes as in the case of Mousetrap or Hedgehog projectiles; by proximity fuzes, as in the case of Mk 8 and Mk 14 depth charges; or by depth fuzes, as in the case of conventional depth charges or “Squid.” If the attacks illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 are to be successful, the charges must explode sufficiently close to the submarine either to rupture its pressure hull and cause immediate sinking or to damage the hull sufficiently to force it to the surface where it can be sunk by gunfire or ramming.The factors determining the probability of success in an attack can be grouped in two general categories: attack errors on the one hand and weapon lethality on the other. The first problem encountered in examining the attack errors in detail is the estimation of errors involved in localization. Ranges and bearings on the submarine are obtained by sonar, which is subject to certain disturbances and limitations.

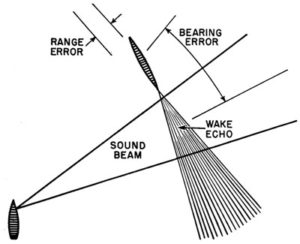

In the first place, echoes are obtained not only from the submarine but from its wake, from water disturbances caused by previously exploded charges, from the wakes of surface vessels, from the ocean floor (in shallow water), and occasionally from the surface of the water. A good sonar operator is not easily led into thinking that these spurious echoes originate from the submarine itself, but it is inevitable that a certain amount of error and confusion creeps into range and bearing information. In addition, an inexperienced sonar operator may easily mistake a false target for the submarine and hence bring about an attack which is wholly futile. An indication of the importance of such mistakes is given by Table 1 which shows the frequency of errors in practice ahead-thrown attacks made at sea on “tame” submarines. It will be noted that the percentage of attacks on false targets is considerable even when an actual submarine is known to be in the immediate vicinity.

Even assuming the contact to be on the submarine (or on some wake disturbance near and moving with the submarine), errors in sonar data are by no means negligible. Figure 3 shows how errors in range and bearing may be introduced by the submarine’s wake, as an example. It has been estimated that the average overall bearing errors are about 2 degrees if BDI (bearing deviation indicator involving lobe comparison for accurate bearings) is used and 4 degrees and 5 degrees if cut-on bearing procedures are used. The probable range error under the same conditions has been taken as 11 yd. These estimates include a normal amount of wake echo and other errors usual in sonar operation. These errors are, of course, dependent on sonar conditions and sea state. When sound conditions are bad, the sonar operator is somewhat more likely to make errors. Roll and pitch of the ship in high seas introduce errors for several reasons.

Present sound gear is not stabilized, so that violent roll and pitch introduce errors in the bearing recorded and also make it difficult for the operator to keep the projector trained on the target. In addition, operator efficiency is reduced when the operator is training the gear with one hand, holding on to the bulkhead with the other, and combating seasickness at the same time. The importance of such factors can hardly be determined theoretically, but operational data on the overall effect of these variables will be presented in a later section.

FIGURE 3. Errors introduced by wake echo.

FIGURE 3. Errors introduced by wake echo.

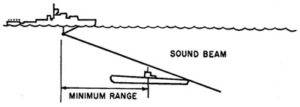

One of the most serious limitations on sonar information is the minimum range at which it can be obtained. Figure 4 illustrates the reasons for this minimum range with present United States sonar. Because of the limited depression angle of the sound beam, the submarine can pass under it. This causes the ship to conduct the final part of a stern-dropped attack after contact with the target has been lost.

FIGURE 4. Minimum range on a deep submarine.”

The Absence of Proof

As the photo on the left illustrates, a sonarman’s workstation was hardly an ergonomic paradise. Aside from a lack of creature comforts, it’s also abundantly clear from this technical discussion that sinking a submarine is a highly complex and deliberate, though problematic exercise comprised of a variety of technologies, sciences and individual competencies; it wasn’t really wasn’t as simple as winning a game of “Battleship” was it, LRH?

As the photo on the left illustrates, a sonarman’s workstation was hardly an ergonomic paradise. Aside from a lack of creature comforts, it’s also abundantly clear from this technical discussion that sinking a submarine is a highly complex and deliberate, though problematic exercise comprised of a variety of technologies, sciences and individual competencies; it wasn’t really wasn’t as simple as winning a game of “Battleship” was it, LRH?

Nor was Hubbard operating in a vacuum. During his attack, he expressed frustration about the reliability of his detection gear, and eventually had to coordinate with the USN ASW K-class blimps that were called to the scene; he was further compelled to enlist the reluctant assistance of several US Coast Guard cutters and additional sub hunters. While the cutters and sub hunters all had similar SONAR to that of the 815, it was the blimp’s magnetic anomaly detection gear or MAD, that Hubbard would claim validated the presence of his targets. MAD uses variations in the earth’s magnetic field as a means to detect ferromagnetic objects such as submarines and was often a preferred alternative to SONAR and other acoustic methods:

“Magnetic anomaly detectors employed to detect submarines during World War II harnessed the fluxgate magnetometer, an inexpensive and easy to use technology developed in the 1930s by Victor Vacquier of Gulf Oil for finding ore deposits.MAD gear was used by both Japanese and U.S. anti-submarine forces, either towed by ship or mounted in aircraft to detect shallow submerged enemy submarines. The Japanese called the technology jikitanchiki (磁気探知機, “Magnetic Detector”). After the war, the U.S. Navy continued to develop MAD gear as a parallel development with sonar detection technologies.”

Into this tactical and technological uncertainty we now introduce Mother Nature. It was a well-known fact that the sea bed in the battle area contained magnetic deposits, which would have disrupted the MAD sensor on the ASW blimps as well as causing false or inaccurate SONAR readings on the cutters, PCs and SCs that responded. Furthermore, the sea off the coast of Oregon is quite deep and very cold, even in Spring, due to the Coriolis effect. Salinity, temperature, currents, and depth all influence modern SONAR, so these factors would have undoubtedly had a detrimental effect on the simpler systems of WWII. Chris Owen also notes that:

“Bizarrely, crustaceans such as snapping shrimps were a frequent cause of false alarms; the US Navy’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Bulletin had to publish articles on the distribution and habits of such underwater fauna to diminish the number of erroneous contacts.”

This naturally occurring magnetic deposit would later prove to be a key issue in the official command investigation into Hubbard’s claims.

So Just What the Heck Was Our Hero Shooting At?

We’ll now consider the alleged “target,” what Hubbard would initially describe as a Japanese mine-laying submarine. He states in his after-action report that:

“it is specifically claimed that one submarine, presumably Japanese, possibly a mine-layer, was damaged beyond ability to leave the scene and that one submarine, presumably Japanese, possibly a mine layer, was damaged beyond ability to return to its base …”

Later, in a 1957 lecture to Scientologists, he specifically states he sunk the IJN submarine I-76, only this time, somewhat correctly labeling it as a “trans-Pacific” submarine rather than as a mine-layer:

“I dropped the I-76 or the Imperial Japanese Navy Trans-Pacific Submarine down into the mouth of the Columbia River, dead duck. And it went down with a resounding furor. And that was that. I never thought about it again particularly except to get mad at all the admirals I had to make reports to because of this thing, see? This was one out of seventy-nine separate actions that I had to do with. And it had no significance, see?

But the other day I was kind of tired, and my dad suddenly sprung on me the fact that my submarine had been causing a tremendous amount of difficulty in the mouth of the Columbia River. Hadn’t thought about this thing for years. Of course, it’s all shot to ribbons, this thing. It’s got jagged steel sticking out at all ends and angles, and it’s a big submarine! It’s a — I don’t know, about the size of the first Narwhal that we built. And the fishermen coming in there and fishing are dragging their nets around in that area, and it’s just tearing their nets to ribbons — they’ve even hired a civilian contractor to try to blow the thing up and get it the devil out of there — and has evidently been raising bob with postwar fishing here for more years than I’d care to count.” Hubbard, “Auditing Techniques — Games Conditions”, lecture of 1 February 1957

We can begin by immediately debunking one of Hubbard’s most obvious lies, that of being near the mouth of the Columbia river when he engaged his mythical enemy; he was not even close, as Cape Lookout is some 70 miles south of the Columbia near Tillamook. As to getting “mad at all the admirals,” I doubt Admiral Frank “Jack” Fletcher, (more of whom later), would brook any sort of attitude from Hubbard.

The claim of “one out of seventy-nine separate actions…” is patently absurd on its face and this lie needs no further explanation. He’s actually spot-on when he says “his” submarine was “about the size of the first Narwhal that we built.” The USS Narwhal, (SS-167), built was launched in 1928 as a “V-boat,” a type that was not in a specific design class. It was exactly the same length as the I-76/176 at 346’ though slightly larger in diameter. The mention of the Narwhal is a classic example of Hubbard using a little bit of truth to validate a bigger lie, and there are many more like this to come in this story and later in his life.

The I-76/176 was an IJN Type KD7 Kadai (“Task”)-type long-range cruiser submarine, of which only 10 were built during the war. It sailed with a complement of 86 officers and men, had a surface range of 8,000 nautical miles (NM), could dive to a depth of 260 ft and were armed with 12 of the best sub-launched torpedoes of the war, the Type-95, a single 120mm deck gun, and two Type 96 25mm anti-aircraft cannons. It was NOT a mine-layer; the Japanese only built 4 dedicated mine-laying submarines, the Type KRS, numbered I-21 to I-24 (later I-121 to I-124). In reality, the I-124 was sunk off the coast of Darwin by the USS Edsall on January 20th, 1942 (9 days after Hubbard had arrived in Brisbane and long before he assumed his first command (but we digress…). As an aside, it would have been an incredible twist of fate, if the I-124 had not been sunk by the Edsall, only to then be sunk by Hubbard off the Oregon coast a year later!

Crucial to debunking Hubbard’s tale is the fact that the KD7’s never sailed East of Hawaii and operated primarily from the IJN base on Truk in the Caroline Islands, some 5,500 NM southwest of the Oregon coast. It would have been madness for a KD7 to roam that far northeast for so little benefit as there wasn’t that much merchant traffic to target. Only 10 KD7s were built, so the probability of one, let alone two, of these highly effective subs being off the Oregon coast at the same time would have been statistically remote if not impossible. Then there’s the fact that the I-76/I176s weren’t even minelayers, so once again, Hubbardian hyperbole rules the day in lieu of the truth.

Action Stations!

Aside from the geospatial and tactical absurdities of his claim, let’s look at the physical composition and performance of the target from a SONAR and surface identification perspective: KD7’s were large submarines with prominent conning towers, complete with large hinomaru (“rising sun”) IJN insignia on either side. They displaced (weighed) 1,833 tons, were 346 ft long, had a beam (width) of 27 ft, and a draft (distance from waterline to bottom of hull/keel) of 15 ft. The KRS-class mine-layers were similar in size and configuration, the only considerable difference being in length, as they were 50 ft shorter than the KD7s. In either case, we’re talking about a significant underwater or surface mass as a SONAR target. Below are pictures of the I-176, a KD7-class sub (on the top) and a KRS class minelayer (on the bottom):

Lastly, as the final factor debunking Hubbard’s claims about submarine type, there’s the fact that postwar analysis by the British Admiralty and the US Navy of captured IJN records account for all of its vessels. There is no record of any Japanese submarine losses off the Western coast of the contiguous United States during the whole of the war. IJN records show that the I-176 was destroyed off Buka Island in the western Pacific by Fletcher-class destroyers USS Franks (DD-554), USS Haggard (DD-555), and USS Johnston (DD-557) on 16 May 1944. Let’s now return to the tale of the chase…

Lastly, as the final factor debunking Hubbard’s claims about submarine type, there’s the fact that postwar analysis by the British Admiralty and the US Navy of captured IJN records account for all of its vessels. There is no record of any Japanese submarine losses off the Western coast of the contiguous United States during the whole of the war. IJN records show that the I-176 was destroyed off Buka Island in the western Pacific by Fletcher-class destroyers USS Franks (DD-554), USS Haggard (DD-555), and USS Johnston (DD-557) on 16 May 1944. Let’s now return to the tale of the chase…

Naval ASW doctrine was evolving rapidly during the period that Hubbard assumed command of the PC-815. With his recent training at SCTC and with fleet bulletins arriving daily, he would have been exposed to the vast flow of ASW tactical and technical information emanating from the CNO. However, it’s clear that in his rush to prove himself in combat, he appears to have ignored much of the contemporary ASW doctrine then available as well as forgetting a host of fundamental leadership principles during those 3 days in May. His erratic behavior under duress confirms that Hubbard’s misreading of the initial SONAR returns, and his chaotic actions during his seemingly random series of attacks were no aberration. His poor grasp of command responsibilities, when combined with his lack of understanding environmental, tactical, and organizational factors, resulted in a recipe for disaster that is reflected in both the historical timeline of the attack and his own unauthorized, novel-like after-action report.

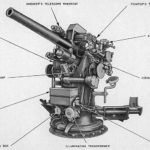

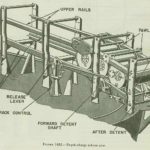

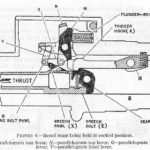

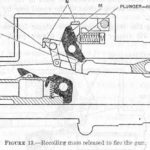

Counter to standard operating procedures (SOPs), Hubbard does not note the precise time of his first attack after the initial SONAR contact at 0340 hours, though he is more diligent in noting the time of subsequent attacks. Hubbard initially used a depth charge launcher known as a “K-gun” and three “rolling” (ie. rack-launched) depth charges. In his report he states that “structural charges were in the K-guns and did not explode” (structural charges are set with a safety proximity fuse that limits detonation if used too close to a ship’s hull). Here are illustrations of the primary weapons carried by a PC-461 class patrol craft:

Hubbard goes on to state that “the three charges rolled exploded at their settings [sic] two were set to explode at 100 feet and one at 50 feet. The contact was lost at 100 yards indicating a target depth of 100 feet.” He notes yet another attack at 0357 hours, this time using both K-guns and depth charges, as “the target was found to be turning back towards the depth charge distance.”

The authorized ASW reporting format is illustrated below on the left, and the first page of Hubbard’s own format on the right:

Hubbard’s own 16 page narrative format, as Chris Owen notes, “reads more like one of his pulp-fiction stories”:

“Proceeding southward just inside the steamer track an echo-ranging contact was made by the soundman then on duty . . . The Commanding Officer had the conn and immediately slowed all engines to ahead one third to better echo-ranging conditions, and placed the contact dead ahead, 500 yards away.

The first contact was very good. The target was moving left and away. The bearing was clear. The night was moonlit and the sea was flat calm . . . The USS PC-815 closed in to 360 yards, meanwhile sounding general quarters . . . Contact was regained at 800 yards and was held on the starboard beam while further investigation was made. Screws were present and distinct as before. The bearing was still clear. Smoke signal identification was watched for closely and when none appeared it was concluded the target must not be a friendly submarine.

All engines were brought up to speed 15 knots and the target was brought dead ahead . . .”

Hubbard notes that “the night (or, given it was 0340, correctly noted in naval terms as astronomical twilight) was moonlit and the sea was flat calm.” It should be noted that submarines of the day used batteries for power while submerged, and valued such ideal conditions to surface and recharge their batteries as well as to ventilate their extremely hot, stuffy hulls. It was also a preferred hunting time to use their deck guns against merchant shipping as a means to conserve torpedoes, as well as for ocean transit; silhouetting a target against the moonlight almost guaranteed a hit.

It’s also important to keep in mind that the average maximum submerged duration for long-range subs like the KD7s, was around 48 hours at 2 knots, hence the importance of covert night-time surface operations for mobility. Thus the chances of Hubbard encountering a submerged submarine in the dark were far less than finding one on the surface at the time of the alleged encounter.

We now return to Chris’ narrative:

“At this point, Hubbard’s military terseness slipped completely:

The ship, sleepy and sceptical, had come to their guns swiftly and without error. No one, including the Commanding Officer, could readily credit the existence of an enemy submarine here on the steamer track and all soundmen, now on the bridge, were attempting to argue the echo-ranging equipment and chemical recorder out of such a fantastic idea …”

“The ship, sleepy and sceptical, had come to their guns swiftly and without error.”

Besides sounding like a quote from a badly navalized version of The Old Man and the Sea, it exposes a fundamental lack of discipline on the part of Hubbard’s sonarmen: why were they on the bridge “arguing” about the accuracy of the SONAR equipment, rather than at their battle stations monitoring the contact? After all, even allowing for a margin of error, this is a significant sized contact if “legitimate,“ especially at such short range. He says the guns were manned, but what about those manning the depth charge racks and K-guns, a far more crucial weapon at this early stage of the attack? A deck gun is only effective once the sub has surfaced, and while the gun team was most likely at general quarters, it seems an odd way to describe the ship’s combat readiness.

Owen continues:

“At 0450, a target on the surface was spotted and Hubbard gave the order to open fire on it. His crew responded with “astonishing accuracy, bursts and shells converging on the target.” It turned out to be no more than a floating log, but Hubbard thought it was good for the morale of the gunners to ensure that the newly-installed guns worked.

The USS PC-815 mounted four further attacks on the elusive submarine in the hope of forcing it to the surface, without success. At the end of the sixth attack the ship’s supply of depth charges was exhausted. Urgent signals requesting more ammunition at first met with no response.”

Hubbard doesn’t state who spotted the target; however, the bigger question is how do we go from a submerged contact to a surface contact without a plausible explanation, given that Hubbard, in his after-action report says the PC-815 lost contact after its last depth charge attack sometime after 0400?

Also, rather than staying submerged, why would a sub suddenly surface at 0450 if it weren’t damaged? Why unnecessarily expose itself to gunfire? The incongruities mount as we note in his report:

“At 0450, with dawn breaking over a glassy sea, a lookout sighted a dark object about 700 yards from the ship on the starboard beam. When inspected the object seemed to be moving. No definite conclusion could be reached as to the identity of the object and the range was closed. Although very probably this object was a floating log no chances were taken and the target was used to test the guns which had not been heretofore fired structurally.”

Remember it’s late May, so at 0450, the ambient light “with dawn breaking over a glassy sea” provides superb visibility conditions. In the days before night vision devices, naval binoculars were optimized for light gathering ability with observers trained to use their own keen vision in concert with these high-quality optics. (As an aside, the Japanese had the best quality night vision binoculars of the war, and when combined with the IJN’s superiority in night fighting tactics and world-beating “long-lance” torpedoes, constantly gave the Allies a bloody nose in night surface actions, particularly in the great naval battles around Guadalcanal). It would appear Hubbard couches incompetence with a “training opportunity;” yet given these ideal visibility conditions, it’s inconceivable a log could have been mistaken for the conning tower of a submarine at such short range.

As for citing the apparent motion of the object as proof that he correctly targeted a submarine, it appears that Hubbard forgot about ocean currents, which can move a log as well as they can move a ship. Then we have “the morale of the gunners;” I would think a fruitless exercise in arboreal slaughter would have had the opposite effect, especially as they apparently missed the “target.”

At this juncture in Hubbard’s combat narrative, it’s surprising that his buddy, XO (executive officer) Lt. Thomas Mouton, receives the praise he does, given the XO was responsible for the ship’s combat readiness. The PC-815’s gunnery appears to have been lacking, and her sonarmen appear to have been wanting in both detection skills and overall combat discipline, so Hubbard would have been justified in censuring Moulton. While Hubbard as skipper holds ultimate responsibility for her performance, Moulton was directly responsible for the tactical and weapons proficiency of the 815, yet Hubbard untypically makes no mention of his apparent failings.

Owen now introduces some new players into the timeline:

“At 0906, two US Navy blimps, K-39 and K-33, appeared on the scene to help with the search. By noon, Hubbard believed that the submarine was disabled in some way, or at least unable to launch its torpedoes, since the PC-815, lying to in a smooth sea, presented an easy target and had not been attacked. In the early afternoon a second subchaser, the USS SC-536, arrived but was unable to make contact with the target.”

The sun’s now up, further enhancing already superb visibility, and with the highly effective K-series blimps now on station, Hubbard’s target surveillance and acquisition abilities are enhanced by aerial observation. What more could a skipper want in hunting a sub?

These blimps had a variety of ways to communicate with surface vessels; the fact there’s no mention in their skipper’s after-action report of having radioed a sighting of a “disabled” sub to the PC-815 is telling. Somewhat spitefully, Hubbard takes the blimps to task in his after-action report for “errors in their concept of distance” though he does make reference to their communication in the “Radio log” addendum. Here’s a picture of a K-series ASW blimp in action:

Given the ideal sea and visibility conditions, and the fact a disabled (not destroyed) sub would most likely not have been at crash depth, had a sub actually existed, the blimp crew would have easily seen the outline of a 346-foot sub under the relatively clear, calm water. There’s also no doubt the skipper of the SC-536 would have interrogated the blimp crew for a read on the situation, as well as using its own SONAR to triangulate on the 815’s contact, so the fact the SC-536 comes up empty-handed further exposes the farce of Hubbard’s scenario. Owen now describes additional questionable tactics by Hubbard:

Given the ideal sea and visibility conditions, and the fact a disabled (not destroyed) sub would most likely not have been at crash depth, had a sub actually existed, the blimp crew would have easily seen the outline of a 346-foot sub under the relatively clear, calm water. There’s also no doubt the skipper of the SC-536 would have interrogated the blimp crew for a read on the situation, as well as using its own SONAR to triangulate on the 815’s contact, so the fact the SC-536 comes up empty-handed further exposes the farce of Hubbard’s scenario. Owen now describes additional questionable tactics by Hubbard:

“On the bridge of PC-815, Hubbard led the other ship on an attack run, blowing a whistle to signal when to drop its depth charges. The results (per Hubbard) were encouraging:

The observation blimps began to sight oil and air bubbles in the vicinity of the last attack, and finally a periscope. This ship also sighted air bubbles . . . At 1606 oil was reported again and this ship saw oil. Great air boils were seen and the sound of blowing tanks was reported by the soundman . . . All guns were now manned with great attention as it was supposed that the sub was trying to surface. Everyone was very calm, gunners joking about who would get in the first shot.”

Hubbard’s use of a whistle to signal his depth charge crew is curious, as given the noise of combat, it would needed to have been quite the loud whistle to have been heard above the din. However, why use a whistle in the first place, when there would have been a talker on the depth charge crew relaying instructions to and from the bridge for this very reason?

Every weapon station has a talker (see photo on left), so the use of a whistle seems quaint and inefficient at best, massively unworkable at worst. As the forward 3”/50 and rear 40 mm Bofors guns were some distance from the bridge, how does he know everyone was “very calm” or for that matter, how does he hear his gunners “joking about who should get the first shot”? If such comic banter was present on the ship’s combat voice circuit, it indicates poor radio discipline and a serious lack of attentiveness.

Every weapon station has a talker (see photo on left), so the use of a whistle seems quaint and inefficient at best, massively unworkable at worst. As the forward 3”/50 and rear 40 mm Bofors guns were some distance from the bridge, how does he know everyone was “very calm” or for that matter, how does he hear his gunners “joking about who should get the first shot”? If such comic banter was present on the ship’s combat voice circuit, it indicates poor radio discipline and a serious lack of attentiveness.

All We Need is More Depth Charges!

Hubbard states that the blimps “began to sight oil and air bubbles…” yet the after-action reports of both blimp skippers make no mention of this. Outside the fact there was nothing to see, ASW blimps typically worked at an altitude anywhere from 500 to 1,000 ft when actively hunting a sub, so seeing bubbles while at altitude may have been problematic, though spotting an oil slick would have been very easy.

More’s the point that the unconfirmed trail of bubbles Hubbard describes is insufficient evidence of the sinking of a 346 ft sub with 86 men aboard and that contains some 300 tons of diesel oil. Much of the evidence that remains of a destroyed submarine depends on how it was attacked. Also, the effectiveness of depth charges varied, as the following overview from NavWeaps, a forum for naval history researchers, illustrates:

“In the first few months of the war only 5 percent of all depth charge attacks were successful. Normal combat conditions reduced that figure to 3 percent. Combat records showed that in early 1942 the lethal probability of a single depth charge pattern (barrage) was about 3 percent and five attacks would raise the chance of a kill to about 10 percent. The possibility of inflicting significant damage to a submarine was about 30 percent after five attacks. By the end of 1943, better weapons and tactics had improved these figures such that about 30 percent of all detected submarines suffered at least some damage and 20 percent were killed. By the last year of the war, at least 35 percent of all submarines attacked were being damaged while 30 percent were killed. In mid-1944, the USN was claiming an 8 percent kill rate with a single Hedgehog pattern. By the middle of 1945, that figure had risen to 10 percent.

In the Atlantic Theater, US surface ships sank 60 submarines, shore-based aircraft sank 54, ship-borne aircraft sank 32 and 40 were destroyed by bombing raids on yards and bases. In the Pacific Theater, surface ships sank 60 Japanese submarines, shore-based aircraft sank 3.5 and ship-borne aircraft sank another 9.5.”

Depth charges kill a sub via concussive as much as kinetic (explosive) force; depending on the contact depth, the use of any additional ordnance such as aerial bombs or surface shelling, and the resultant lethality of any secondary explosions, the evidence of a kill can vary. In Hubbard’s example, some 37 depth charges were dropped. If that barrage was effective, it would have undoubtedly split the sub’s hull, resulting in not only a significant oil slick, but also a large debris field. In our opinion, it’s clear that what was in Hubbard’s eyes was an oil slick and air bubbles was most likely either the result of reflected sunlight, marine debris from depth charge explosions, or a combination of the two.

His “periscope” is most likely a branch jutting off a submerged log, given that the Columbia River delivers a great deal of logging waste into the currents off the Oregon coast, and causes marine hazards far out to sea and down the coast.

Furthermore, a submarine in distress would hardly be undertaking a controlled surfacing to periscope depth; it would be crash-diving to escape the threat, or if unable to dive, it would most likely expose not only its periscope, but a good portion of its conning tower, given its partial ballast from a damaged hull, as shown in the following photos of partially submerged damaged U-boats:

Having now engaged and supposedly sunk the first contact, his sonarman apparently locates yet another contact as Chris describes:

“The PC-815 now made a startling discovery: there was not just one submarine but two! The second one was discovered some 420 yards away, drawing away at about four knots.

Keep in mind that there are now two ships in the area with a third, a Coast Guard cutter, on the way, so it’s getting crowded on the surface. Sound is amplified underwater, thus more screw “noise” arrives in the form of a second Coast Guard cutter, so we now have four vessels in the immediate area of operation, along with the two blimps overhead. Between the MAD activity from the blimps and the SONAR activity of four (soon to be five) ships, there’s now considerable noise clutter at play amongst all the detection devices in use, let alone the interference from magnetic deposits in the sea bed that could cause all sorts of distortion:

“At 1646, a Coast Guard patrol boat brought in further supplies of ammunition. Manoeuvring alongside, twenty-seven depth charges were transferred on to the USS PC-815 and made ready for firing. Not long afterwards, a second Coast Guard patrol boat, the Bonham arrived, followed by another subchaser, the USS SC-537. There was now a total of five ships and two observation blimps involved in the search for the enemy submarines off the coast of Oregon. Not all of the ships seemed to be as keen as the PC-815, however, as Hubbard complained bitterly in his action report:

During the night of the 21st when this vessel was attempting to make a routine sweep and search in the standard sweep formation, neither the SC537 nor the USSCG Bonham showed any understanding whatever and refused by their actions to cooperate. It is later understood that the Bonham had a top speed of 9.2 although she reported her speed to us as 12 and that she was under the supposition that she would blow herself up if she dropped charges. The SC537 had one contact which she reported during the following day and failed to prosecute it. The SC537 left the scene with her racks full of charges although the SC536 and the PC815 had exhausted all theirs. Echo range was never more than about 900 yards in this shallow water and despite orders neither vessel would close in to this with one exception, as noted in the attacks as of the following morning.”

Hubbard had now been on this fruitless quest for two days running. His crew is most likely exhausted, hungry and operating less than optimally, most likely on coffee and benzedrine, a commonly issued stimulant used during the war. We can also assume that Hubbard is most likely wired to the gills too, as he never mentions standing down nor being party to any form of relief during the entire action. This would also account for his unreasoned attempts to continue his attack late on the second day, and could explain his churlishness towards his fellow skippers.

He also questions why “neither the SC537 nor the USSCG Bonham showed any understanding whatever and refused by their actions to cooperate.” Here we see classic Hubbard projection: it’s not a question of “showing understanding;“ it’s the objective outcome from having analyzed the tactical and logistical realities at hand. Such a statement simply reinforces the fact that Hubbard never grasped the selflessness of command nor the practical realities of battle.

The rest of his after-action is rife with this sort of editorializing and whining, so it’s easy to see why the other skippers involved were hesitant to engage in this fantasy fight. For example, the USS Bonham, WSC-129 was an Active-class Coast Guard patrol boat, that was repurposed in 1942 as a subchaser. With only a 3” gun and two depth charge racks, she lacked much of the PC-815’s ASW capabilities, thus Hubbard should have taken her limitations into account. Here are two photos comparing the PC-815 to the Bonham; note the limited space on the Bonham’s fantail for depth charge rack installation (though later in the war the Active-class PCs would be upgunned closer to that of a 461-class patrol craft):

He mentions earlier that the water where the PC-815 was echo ranging was “shallow,” yet as Owen quotes below, he also states “we considered from her (the sub’s) failure to surface that she had gone down in 90 fathoms,” which is 540 ft deep, hardly shallow water; so what’s it to be, shallow or deep water:

“The small fleet continued searching throughout the night and into the following day. The attacks continued, but still no there was no sign of either submarine having been damaged or destroyed. Hubbard was not discouraged, even after 34 fruitless hours:

Because we had three times found two sub targets on the previous day, we considered from her failure to surface that she had gone down in 90 fathoms. The other still had batteries well up for it made good speed in subsequent attacks (three to six knots).”

As it appears Hubbard can’t discern between shallow and deep water, how does he then determine his SONAR is ranging accurately or if his depth charges have been set for the appropriate detonation depth? It’s an amazing lapse in fundamentals considering what he’s been tasked with!

The 815 is then diverted north by a false report of a second submarine (which in reality was a fishing boat) and now “flying north,” the fruitless search continued, until Hubbard appears to spot a submarine attempting to surface at 0700 hours on the morning of May 21st:

“Suddenly a boil of orange colored oil, very thick, came to the surface immediately on our port bow . . . The Commanding Officer came forward on the double and saw a second boil of orange oil rising on the other side of the first. The soundman was loudly reporting that he heard tanks being blown on the port bow.

Every man on the bridge and flying bridge then saw the periscope, moving from right to left, rising up through the first oil boil to a height of about two feet. The barrel and lens of the instrument were unmistakable . . . On the appearance of the periscope, both gunners fired straight into the periscope, range about 50 yards. The periscope vanished in an explosion of 20mm bullets.”

What’s interesting is that Hubbard makes no distinction as to the source of this “boil of orange colored oil, very thick…” Is it from submarine number one, or submarine number two? What’s more suspect is that the fuel is orange. Bunker fuel oil is a very dark, sludgy brown in color, and not orangish:

This important detail casts further doubts about the accuracy of his novel-like narrative, more so when narcissistically describing himself in the third person: “the Commanding Officer came forward on the double and saw a second boil of orange rising on the other side of the first.” My immediate reaction when reading this is to think “why wasn’t he forward (i.e., on the bridge) in the first place? Perhaps he was arguing with his sonarman about the source of the ‘tanks being blown on the port bow…’.”

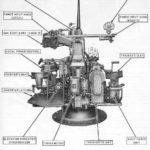

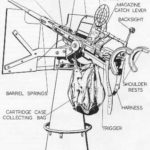

Then we have the lurid detail of a periscope moving through the oil, “rising to a height of two feet. The barrel and lens of the instrument were unmistakable.” Seen at a range of 50 yards, it supposedly vanishes “in an explosion of 20mm bullets.” Given the state of the crew’s earlier deck gunnery, hitting a moving cylinder that’s roughly 5” in diameter from a rolling platform with a large-caliber bucking weapon would be quite a feat, even with those large rounds from the reliable Oerlikon 20mm cannon and optical sights. Here’s a photo of a 20 mm Oerlikon cannon, its rounds, and its alleged target:

However, what’s more troubling is his use of the Oerlikon in the first place. Navy doctrine teaches that light caliber weapons like the Oerlikon are for use against aircraft, not surface ships; that’s what his 3”/50 main gun is for. Here again Hubbard violates tactical doctrine. He does later imply in his after-action report that his goal in excessive depth charging was to get the sub to the surface, so as to finish her with gunfire (with the 3”/50 we would hope, so he’s at least giving lip service to SOP).

Despite all the PC-815’s martial bravado, Hubbard’s fight was soon coming to an uneventful end. Owen details his last attack, his frustrations about a lack of support, and the general consensus among Hubbard’s fellow PC/SC skippers as to their hesitancy in continuing any further action. Let’s look at this final “shot” as it were:

“A last attack run was executed by the PC-815 and SC-536, exhausting their last depth charges. As the ships continued to search for the elusive submarine, another subchaser, the PC-788, was sighted and cajoled into joining the search, although her captain ‘protested very strongly against helping, … requesting continually to be allowed to be secured.’ Frustratingly for Hubbard, even after the PC-815 and SC-536 had dropped around a hundred depth charges, the sonar contact continued to be present but stationary on the sea bottom. The PC-536’s regular commanding officer arrived on the scene and, taking charge from his executive officer, promptly curtailed his ship’s involvement in Hubbard’s search.”

Given the reaction of the 788’s skipper, one can surmise there was back-channel communications going on among the other skippers as to the futility of Hubbard’s fight and questionable claims. The 788’s skipper’s hesitance is understandable, as he would have had to justify his ammunition expenditures as well as filing an after-action report that would have been embarrassing at best, given the results to date.

Hubbard’s obstinance in the matter is further demonstrated by his insistence on one final attack, as “the sonar contact continued to be present but stationary on the sea bottom.“ Another tool in the ASW bag is the hydrophone, which is basically an underwater microphone, and was one of the earliest means of detecting submarines, dating from late in WWI. It’s particularly useful in determining if a submarine is breaking up as a result of depth charging, etc. It would appear that the SONAR return in this instance may have in fact been the magnetic deposits on the seabed, rather than a submarine hull.

Hubbard makes no mention in his after-action report about hydrophone usage, yet it could have provided proof of his target’s destruction as it broke apart while sinking, despite the presence of a large magnetic anomaly. Given the amount of explosives expended on either one of the alleged submarines, it stands to reason that significant hull damage with the associated acoustic signature would have occurred at some point and thus been detectable by hydrophone, providing Hubbard some proof of his “kill.”.

Did Hubbard Cover-up A Crew Member’s Gross Negligence? The Oerlikon Lie Exposed

After this last gasp attempt to sink his elusive prey, Hubbard is ordered back to port. Owen details Hubbard’s less than enthusiastic reception at the Astoria naval station:

“At midnight the PC-815 received orders to return to Astoria Naval Station, having been in action for some 68 hours. Hubbard noted that they were welcomed ‘with considerable skepticism. Her records had not been examined, her crew had not been questioned and no qualified report had been made.’

His ship had expended 37 depth charges and had maintained ‘contact with submarines’ for over 55 hours. Three minor casualties were suffered, probably as a result of tiredness affecting the crew’s performance. Hubbard did not mention that he had very nearly suffered a fatality – his executive officer, Thomas Moulton, was nearly shot when the starboard 20mm gun accidentally fired off an entire magazine, without anyone being at the trigger. The gun had been assembled incorrectly by an exhausted gunner and a key part put in backwards.”

In analyzing the circumstances of Hubbard’s description of this “malfunction,” from my perspective as a school-trained armorer in the Marines and my comprehensive understanding of how weapons function in general, this is nonsense; he is covering-up for his own failings and the gross negligence of one of his crewmen. If true, this incident demonstrates a general lack of professionalism aboard the PC-815, reflective more of sincere amateurs and Hubbard’s dilettantish, often incompetent leadership than anything.

Thus I don’t buy his explanation whatsoever of how this weapon malfunctioned, nor the context he provides, nor that a mechanical fault caused the runaway gun that damaged his antenna mast and supposedly almost killed Moulton. In examining the record, let’s first look at the 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun in general, then we’ll dive into a deconstruction of yet another major lie from Hubbard.

The 20 mm Oerlikon automatic cannon was based on a WWI German design and one of WWII’s iconic weapons. It was licensed-built throughout the world, and in WWII, was used extensively by combatants on both sides at sea and on the ground primarily in the anti-aircraft role, and also equipped front line fighter aircraft. It was adopted by the US Navy in 1940, and as historian Kent G. Budge goes on to say:

“…production did not begin until late 1941, and only 379 weapons had been produced by the time war broke out in the Pacific. Manufacture ramped up rapidly thereafter, and by April 1942 there were sufficient weapons to rearm the entire U.S. Fleet, meet new construction requirements, and begin supplying the weapon to auxiliaries and merchant ships. Further production increases were ordered in early 1943 to equip landing craft. Production peaked at 4,693 mounts in September 1943, and total production was 124,734 mounts. Initially costing about $7000 per gun, improvements in mass production brought the price down to $1658 by the end of the war.”

Keep in mind that effective mass-produced weapons like the Oerlikon derive their success from a variety of factors: simple, reliable and robust design traits, excellent lethality proportional to logistical requirements, and most importantly, ease of maintenance, robust tolerances and the ability to quickly remedy simple mechanical faults in combat. All these considerations are what comprise a weapons “system” which is then integrated into the Navy’s fleet logistics chain, a key component of which is the use of “levels” for assigning maintenance duties. These levels are described as unit or Organizational (O-level), Intermediate level (I-level) and Depot level (D-level), with the majority of maintenance beyond daily tasks, such as limited and major repairs on ordnance being done at I- and D-levels. Major combat damage was repaired in dry docks in forward areas such as Ulithi Atoll or in yards such as Pearl Harbor, Mare Island, Bremerton or San Diego on the West Coast.

The complex trigger housing of the Oerlikon would be considered an I-level repair, as would its gyro-stabilized sight (if mounted at the time). Conversely, removing the barrel, action spring or bolt assembly would fall under authorized preventative maintenance tasks, given their simplicity. For example, the barrel only takes 30 seconds to remove, a rarity on a weapon of this size. In accessing the trigger housing group for whatever reason, this sailor was guilty of a serious violation of ordnance handling regulations, as well putting the lives of his shipmates in danger with his actions. Had a superior authorized his actions, it still would have been grossly negligent, and should never have happened. Even if the sailor in question was a qualified armorer, on a small craft, these types of repairs are meant to be undertaken ashore in a armorer’s workshop with specialist tools such as jigs and custom punches.

That’s not to say that these rules weren’t often broken in the more loosely-regulated war zones, though there’s no way this could be argued as necessary off the Oregon coast, especially so close to a well-stocked port facility like the Astoria Naval shipyard. What makes this all the more egregious in Hubbard’s case, is that he’s not marooned on the edge of civilization in some Pacific atoll and forced to improvise. Thus the close proximity of a major repair facility, reinforces the fact there was little or no reason for anyone on his crew to undertake anything but preventative or daily O-level maintenance, such as rust prevention, oiling and servicing of the ship’s power plants and weaponry, or calibrating her radio and sonar gear.

Therefore, given the well-known reliability of the Oerlikon, along with the fact that these weapons had not been fired with any great regularity over the previous two days, why then is this sailor attempting to disassemble a critical component that is never mentioned as faulty, rather than simply cleaning, oiling, and securing the weapon until the PC-815 reached port? It just makes no sense.

Hubbard conveniently does not state how many rounds of 3”/50 or 20 mm ammunition were fired in the “Gunnery Report” section of his after action report, stating only that on Friday, May 21, 1943 at 0704 PC-815:

“Opened fire from all guns at periscope in the center of oil boil. Continued firing until the periscope disappeared.”

This explanation is far more terse than the narrative prose he uses earlier in the operational narrative, wherein he states “the periscope vanished in an explosion of 20mm bullets.” He leaves no hint as to what constitutes an “explosion” as a means to quantify how many rounds were expended or the effect on the target, nor which gun or guns were fired.

The ammo mix in a 60-round Oerlikon magazine (see photo to left) consists of high explosive, high explosive-incendiary, tracer, and ball (copper jacketed lead) in repeat order, so what caused his “explosion” is anyone’s guess. He does however, list in great detail the amount of depth charges he uses, so it’s left to the reader to try and extrapolate his 3”/50 and Oerlikon ammunition usage and its effectiveness, an omission that must have thrilled Admiral Fletcher when he read this fiction. Let’s now return to this mysterious malfunction.

The ammo mix in a 60-round Oerlikon magazine (see photo to left) consists of high explosive, high explosive-incendiary, tracer, and ball (copper jacketed lead) in repeat order, so what caused his “explosion” is anyone’s guess. He does however, list in great detail the amount of depth charges he uses, so it’s left to the reader to try and extrapolate his 3”/50 and Oerlikon ammunition usage and its effectiveness, an omission that must have thrilled Admiral Fletcher when he read this fiction. Let’s now return to this mysterious malfunction.

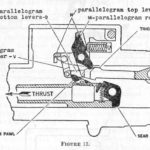

Owen notes that “the gun had been assembled incorrectly by an exhausted gunner and a key part put in backwards;” while Hubbard states in his after-action report that:

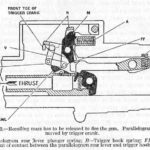

“Failure on the part of a gunner to properly assemble the parallelogram of the starboard 20MM (he reversed it) caused this gun to go off when pointed at the zenith and expend a full magazine, cutting away our antennaes [sic]. The gun was not at the time manned.”

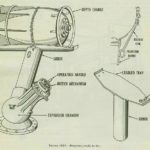

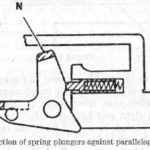

As before, we’ll dissect this statement sentence by sentence, as it’s quite revealing on several levels. In doing so, let’s start with the weapon. In consulting USN Ordnance Pamphlet No. 911, “20 mm. A.A. GUN,” Hubbard’s explanation of a “failure on the part of a gunner to properly assemble the parallelogram of the starboard 20MM (he reversed it) caused this gun to go off…” appears highly unlikely on the surface, given his vague description of the failure.

We’ve already established the provenance and reliability of the Oerlikon, which makes this explanation all the more suspect. As we previously established, the Navy is diligent in documenting the use and care of weapons, a great deal of which includes a constant stream of technical updates and reports from the field. I consulted a variety of sources in locating contemporary maintenance bulletins, from the US Navy, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), and Royal Navy (RN), all of whom used the Oerlikon extensively, and nowhere could I find any mention of a “reversed parallelogram,” let alone it having caused what’s more properly known as a “runaway gun.”

The lack of any reference to a reversed parallelogram is not surprising, as there are actually four discrete parts with “parallelogram” in their respective nomenclature, which are in turn considered part of the trigger mechanism contained in the trigger housing box:

The operator’s manual contains three pages of examples of malfunctions and their causes, only a few of which even refer to one of the various parallelogram parts, nor does not list improper assembly of the “parallelogram” as a known cause for an Oerlikon malfunction. A detailed examination of the functions of the 4 parallelogram parts shows that none of the parts can be “reversed,” given their relationship within the trigger housing. Aside from their physical configuration preventing such an error, even if that had indeed occurred, the gun would not have been able to function at all, let along cycling an entire magazine while unattended. Here’s an example where one of the parallelogram parts in the trigger assembly caused a fault as reported by one of the many training centers throughout the Navy:

“Rear parallelogram lever plunger (OE-1212) sticking so that when top lever (OE-1204) is lifted by the trigger crank (OE-1223), rear lever (OE-1203) is not forced off trigger hook (OE-1216).”

A sticky part is easily remedied through lubrication or filing, unlike a human-induced fault such as the gunners mate supposedly reversing the “parallelogram.” Significantly, the most common cause of Oerlikon misfires are “the result of bent or broken strikers (similar to a firing pin), or by carbon fouling and powder residue clogging the central hole in the breech face piece under the stress of many rounds being fired.”Having now established there are not grounds for a mechanical cause for this mishap, let’s now look at how the Oerlikon itself was configured and positioned when it allegedly started firing all by itself.

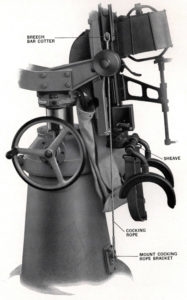

It’s important to note that you don’t just waltz up to an Oerlikon, pull the hammer back and fire the thing. The action spring of an Oerlikon takes 500 foot pounds to cock and requires the gunner to use a rope and pulley mechanism or a lever attached to the rear of the barrel to cock the gun before firing; there is no “charging handle” or the like as found on modern sporting rifles. It is also equipped with an effective safety that mechanically prohibits the trigger from engaging the sear which in turn releases the bolt, thus initiating the firing sequence. The Oerlikon is blowback-operated, which means it obtains energy from the motion of the cartridge case as it’s pushed to the rear of the receiver by the expanding gas created by the ignition of the propellant charge. There’s more involved, but for our purposes, the fact that it fires from an open bolt as a result of its design is an important consideration, as it allows the weapon to be combat ready in a reasonably safe configuration. Note the cocking rope and pulley in this photo:

My first question is that SOP says weapons are to be rendered safe when not at General Quarters, so why was this weapon even loaded and the safety not on in the first place?

My first question is that SOP says weapons are to be rendered safe when not at General Quarters, so why was this weapon even loaded and the safety not on in the first place?

My next question is hypothetical: having incorrectly reassembled the weapon as Hubbard claims, how could the sailor have not noticed that he was unable to cock the weapon, let alone leave it in a condition where it could somehow fire on its own?

Crucially, there’s no way the bolt would have been able to seat properly nor would it have correctly engaged the trigger assembly. Even with a magazine in place, as a blowback operated weapon, the inability of the bolt to lock to the rear as the first step in the firing sequence, would have prevented the weapon from cycling a round, as it needs the combustion energy from firing to complete a firing cycle. Again, how could a properly trained gunner not notice any of these faults?

So supposing it did fire by itself somehow?

Hubbard says the gun “(was) pointed at the zenith and expended a full magazine, cutting away our antennaes [sic].” which means the barrel was pointing straight up when it started firing; he’s rather pretentious here and also incorrect in his use of”zenith” to describe the gun’s position, as proper naval form would have him use degrees/angle/declination, depending on the context.

According to Chris Owen, on May 24th, 1984, former Lt. (jg) Thomas Mouton testified during the Church of Scientology v. Armstrong trial:

“that he was on the mast of the PC-815 when the gun went off, firing until its entire ammunition drum was empty, missing him by a few inches and shooting off the ship’s radio antennae. He later recalled: ‘I was making love to the mast and was almost out to the other side. Looking down the barrel, it looked like it was coming right toward me.’”

The Oerlikon has a muzzle velocity of 2,725 feet per second (FPS), with a projectile weight of 0.5 pounds pushed by a standard charge; thus it is not considered a high velocity weapon, in that its rounds do not maintain a relatively flat trajectory for the duration of their flight.

Depending on the elevation of the muzzle (the end of the barrel), relatively slow projectiles like those of the Oerlikon travel in an ever-increasing parabolic arc. That said, it would have been a straight (flat) shot between the muzzle of Hubbard’s suspect gun and his mast and antenna array; thus given it’s flat trajectory, what could it have hit? Here’s a photo that shows the relationship between the bridge, the platform-mounted Oerlikons to its rear, the ship’s mast, and the main antennas (tall whips just in front of funnel):

Note that the black coverings on the vertical Oerlikons on the platform just behind the bridge on either side of the main mast and how the barrels run parallel to the mast as well as the tall whip antennas on the same platform. Moulton says that he was on the mast, but where? In the small crow’s nest seen in the photo? Or was he climbing on the hand-holds along the back of the mast towards the radar array? His statement that “he was looking down the barrel” is open to interpretation. If he was indeed “making love to the mast,” that would imply he was at the base of the mast or perhaps a little higher.

However, any of those locations would put him a position that was roughly below or parallel to the path of the rounds and not “looking down the barrel.” To realistically do so, he would have needed to be higher on the mast, either in or above the crow’s nest (box-like structure in front of flag jib) to get this perspective. There’s no way a fully elevated Oerlikon, (i.e., at zenith) could hit the main search radar or the main whip antennas, (located on the same platform as the Oerlikons), unless the guns were fully depressed, not at zenith.; There’s also the question of how the gun comes to be horizontal and in motion enough to hit the base section of an antenna that’s 3-4” in diameter. It’s the periscope challenge all over again… Crucially, the mass of an Oerlikon is located to the rear, so even if it were firing by itself, it more than likely would not autonomously assumed a horizontal position. Neither Moulton nor Hubbard are clear on which antennas they’re referring to either, as there are numerous high frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), FM, and ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore radio antennas located all over the ship.